The Weimar Republic

(SPD Poster, 1920)

The Weimar

Republic is the term applied to the period from 1918-1933 in Germany. The

parliamentary system of Weimar, similar to that of Britain, was the first true

democracy in Germany and the ruling party — the Social Democratic Party, a center-left party — sought to unite the masses for democratic means. Despite their goals of

unity, loyalty, and duty, the Social Democratic Party inherited complex and

dire circumstances, which, along with their unpopular actions and efforts to mend the broken country,

made the SPD an easy target for both the more Leftist (Socialism, Communism)

and the Right (Nationalism, Authoritarianism) parties. These issues include:

• Extreme

terms of the Versailles Treaty (Occupation of Rhineland, limitations on German armed and naval forces, prohibition

of weapons, loss of colonies and European

territories, reparation of 226 billion Marks)

• German

Revolution (November 1918-January 1919)

•

Industrialization/modernization

• Economic

crisis (hyperinflation, severe drop in living standard, Great Depression)

• Frequent

political changes (splitting parties uprising and challenging the SPD)

•

Social-cultural changes (national healthcare, mobilization of workers, veteran disability program, etc.)

• Public

disappointment with Capitalism

By the time the SPD controlled the government in 1918, there

were multiple individual parties on both the Right and Left. While every party

recognized the crises facing the Weimar Republic and the German people, each

one had its own solution incongruous with the others.

The Right

The

political right (including the DVNP) propagated the Stab-in-the-Back Myth to fight against the center-left Weimar

Republic and SPD. The Right parties argued that Germany’s first military defeat

(WWI) came at the hands of the socialists and their 1918 revolution, thus, the

crippled status of Germany was directly caused by the ideology of the left.

Because of this, the Right groups cited, all leftist politics, economics, and

even art, was unacceptable and abominable.

The Left

(USPD Poster 1919)

Though the SPD was a leftist party, groups unhappy with the

SPD’s class collaboration and support of WWI split from the party in 1917 to

for new and more extreme left groups (primarily, the USPD and KPD). These

groups, though varying in liberalism from democracy to Marxism, all opposed

the government's handling of WWI (counter groups began to form within the SPD prior to 1917 for this reason), supported the working class (proletariat) and felt further alienated by

their parent party when the SPD used the right-wing paramilitary forces to

suppress any revolutionary uprisings.

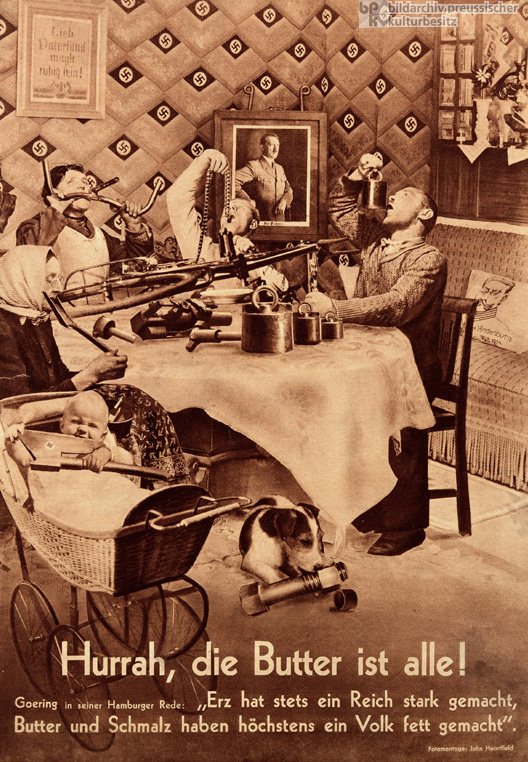

The Left: Art

Artists

from various schools (Dada, Expressionism, Neue Sachlichkeit) sided with the left

groups and used their art as public outcry and commentary against the state of

German society and government. Though many artists within the Bauhaus were left-leaning, its founder Walter Gropius declared it apolitical. It is not included here because its pieces were not created as social/political commentary or criticism.

|

Cut with the Kitchen Knife...

Dada |

• Dada: A group protesting the

bourgeois, nationalism, rationality, and all other institutions and beliefs

developed from the Enlightenment as the cause for the horror and depravity of

modern humanity. Because of this rejection of the traditional and rational, the

Dadaists were opposed to the figuration of its contemporary — Expressionism

• Expressionism: With the

reprehensible results of WWI, both economically and in lives lost,

Expressionists moved from a search for an inward, spiritual enlightenment to an

anational socialism, criticizing the bourgeoisie, capitalism and democratic

means while lauding the resurgence of a “spiritual attitude […] which has

existed for millennia in the history of humanity.” This spiritual attitude is

the Expressionists response and solution to the Dadaists view of the

Enlightenment and also explains why, unlike the Dadaists, the Expressionists

did not reject traditional forms such as the figure.

• Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity): see

Socialism and Dystopia: Neue Sachlichkeit

Images Used

(I was having formatting issues when adding captions)

1. SPD political poster

2. USPD political poster

3. Dawn From in the Shadows, George Grosz, 1920-21

4. Prague Street, Otto Dix, 1920

5. The Orator, Magnus Zeller, c1920

6. Cut With the Kitchen Knife..., Hannah Höch, 1919-20

7. The Widow II, Kathe Kollwitz, 1922

Works Cited

Berger, Stephen. "Germany." The International

Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest: 1500 to the Present. Guntram H.

Herb and David H. Kaplan ed. Vol. 2: 1880-1945. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-Clio,

2008. 609-22. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 22 Nov. 2012.

Lewer, Debbie. "Revolution and the Weimar Avant-Garde:

Contesting the Politics of Art, 1919-1924."Weimar Culture Revisited.

New Yok: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. 1-21. Print.

Peters, Olaf. "Aesthetic Solipsism: The Artist and Politics

in Max Beckmann 1927-1938." Totalitarian Art and Modernity.

Aarhus: Aarhus UP, 2010. 325-45. Print.

Schmidt, Ingo. "Communist Party, Germany." The

International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest: 1500 to the Present.

Immanuel Ness ed. Vol. 2. Malden, MA: Wiley Blackwell, 2009. 826-29.Gale

Virtual Reference Library. Web. 27 Nov. 2012.

Williams, John A. Foreword. Weimar Culture Revisited.

New Yok: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. N. pag. Print.

Article by Catherine Estrada